Character Research Files

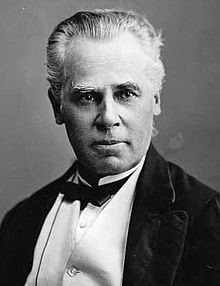

William Avery (Billy) Bishop Jr, Canadian Flying Ace (1894-1956)

Billy Bishop is known for more than just being the name of one of Toronto’s airports. He was Canada and the British Empire’s top flying ace in World War I, having been credited with shooting down 72 enemy aircraft in a profession where pilots were known to have extremely short and deadly careers. During World War II Bishop played a critical role in recruiting new pilots to the Royal Canadian Air Force and in promoting the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, a program which taught Commonwealth aircrews throughout the war, and was a major contributor to the air superiority the Allied Forces experienced over Nazi Germany throughout the war.

Billy Bishop is known for more than just being the name of one of Toronto’s airports. He was Canada and the British Empire’s top flying ace in World War I, having been credited with shooting down 72 enemy aircraft in a profession where pilots were known to have extremely short and deadly careers. During World War II Bishop played a critical role in recruiting new pilots to the Royal Canadian Air Force and in promoting the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, a program which taught Commonwealth aircrews throughout the war, and was a major contributor to the air superiority the Allied Forces experienced over Nazi Germany throughout the war.

Billy Bishop was born in Owen Sound in 1894 to William Bishop Sr, a lawyer, and Margaret Greene, and had two older brothers and a younger sister. His older brother Kilbourn passed away in 1892, two years before Billy was born. As a youth Billy Bishop was an avid outdoorsman, and enjoyed riding horses, shooting, and swimming. He had a clear interest in flying even as a young boy, which became evident when he “built” a flying machine out of an orange crate with bedsheets for wings. He attempted to fly his invention from the roof of the house, and notably ruined his mother’s rose bushes while escaping serious injury.

Bishop attended school in his hometown of Owen Sound before enrolling at Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario, in 1911 at 17 years of age after completing high school. In his senior year, 1914, the First World War broke out and Billy Bishop enlisted in the army along with many of his classmates. Due to his experience horseback riding and his excellent shooting skills, he was given an officer’s rank of Lieutenant and assigned to the cavalry as a member of the Mississauga Horse Regiment.

In August 1914, the Mississauga Horse Regiment was preparing to set sail for England on October 1st of the same year. Bishop was unable to make the journey, however, as he caught pneumonia and was too sick to travel. Bishop was released from the hospital and was reassigned to the 7th Canadian Mounted Rifles in London, Ontario, and set sail to England with his division on June 8, 1915.

One month later, at the Shorncliffe military camp in England, Bishop saw a plane land in a nearby field only to take off a short time later, and he stated that it was this sight that compelled him to take to the skies rather than fighting on the ground. Specifically, Bishop attributed his hatred of trudging through the mud and witnessing the effortlessness at which airplanes could leave the mucky battle below to the ‘summer sunshine’ as his reason for wanting to become a pilot.

Following this life-changing event, Bishop applied for a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps and became an observer on a plane by September 1915. He applied to be an observer because training to be a pilot would take six months and he wanted to bypass this training. By January 1916 he was stationed with a Squadron on the front lines that flew missions deep into Axis territory.

Bishop received his wings in November 1916 and in March 1917 he was sent to the front lines in France. On March 25 he entered his first real air fight, shooting down his first German airplane and barely making it back to base alive. By the end of May Bishop had already racked up 22 casualties.

Bishop’s most famous air exploit took place in the early morning of June 1917. According to him, he flew across enemy lines and shot down three German planes and made it back to his squadron by stealthily flying under his enemies. In August 1917, Bishop was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, the Military Cross, and the Victoria Cross by King George V at Buckingham Palace. One month later his Distinguished Service Order was upgraded, making him one of the most highly decorated participants of World War I.

Billy Bishop took leave in September 1917 to become a successful author, writing a book about his air exploits called Winged Warfare. One month later he married his sweetheart, Margaret Burden. In early 1918 he returned to England to command a new squadron nicknamed the Flying Foxes. With this squadron, Bishop accumulated the remainder of his 72 downed enemy aircraft. When he returned to England in August 1918, Lieutenant Colonel Bishop was made the commander of the Canadian Wing of the Royal Air Force.

Following the War, Billy Bishop returned to Canada and gave a lecture tour across North America, speaking mainly about his wartime adventures and exploits. He also was a successful businessman until the Great Depression wiped out much of his wealth in 1929.

In 1934, Bishop took pilot training to be recertified his flying license, and was made an Honourary Air Vice Marshal by Prime Minister King, where he advocated for an expansion of the RCAF. When Canada declared war against Nazi Germany in September 1939, the Canadian government agreed to a proposal whereby Canada became the training centre for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, and Billy Bishop became head of recruiting for the RCAF in January 1940.

This role took a toll on Bishop, and in 1942 he was hospitalized with pancreas issues that required surgery. He returned to recruiting in March 1943 and completed a second popular book called Winged Peace in 1944. Following the war Bishop moved to Montreal and entered into the oil business in a semi-retired capacity. He enjoyed spending hours reading in his private library and became an avid ice, soap, and wood carver.

When the Korean War began in 1950, Bishop volunteered to serve as a pilot at 56 years old, but was politely declined. In 1952 he began spending his winters in Florida, and he died peacefully in his sleep at his Florida home in 1956. 25,000 people attended his funeral in Toronto.

Despite his heroic status in Canadian history, Billy Bishop’s legacy is not without controversy. Throughout the years many have challenged his claims of heroic feats, and even Bishop himself admitted that he embellished some of his flying exploits for his books. In particular, due to gaps in British and German records, and the destruction of some in WWII, not all of Bishops 72 kills could be confirmed, and it is unlikely that they ever will be.

Booker T. Washington (1856-1915)

Early Life: Born into Slavery

Early Life: Born into Slavery

- Booker T. Washington was born in 1856 into slavery. His mother, Jane, was an enslaved African-American woman in southwest Virginia, and his father is said to be a white man who lived on a neighbouring plantation. Booker never knew his father, and as such Booker said his father never played an emotional role in his life.

- At an early age, Booker went to work carrying grain to the plantation’s mill. Toting 100-pound sacks was hard work for a small, young boy, and he was sometimes beaten for not performing his duties to the liking of his masters

Freedom after the Civil War

- As a boy of about nine in Virginia, Booker and his family gained freedom under the Emancipation Proclamation as US troops occupied their region in Virginia.

- After the Civil War, Booker and his mother moved to Malden, West Virginia, where she married Washington Ferguson, himself a recently freed man. The family was very poor, and 9-year-old Booker went to work in the nearby salt furnaces with his stepfather instead of going to school.

- Booker’s mother noticed his interest in learning and got him a book from which he learned the alphabet as well as how to read and write basic words. Because he was working, he got up nearly every morning at 4 a.m. to practice and study.

- At about this time, Booker took on the name of his stepfather for his last name, Washington.

- In 1866, Booker T. Washington got a job as a houseboy for Viola Ruffner, the wife of coal mine owner Lewis Ruffner. Mrs. Ruffner was strict with her servants, especially boys. But she saw something in Booker—his maturity, intelligence and integrity—and soon warmed up to him.

- Booker worked for Ms. Ruffner for two years, and understanding his desire for a formal education she allowed him to go to school for an hour a day during the winter months.

Formal Education and Tuskeegee

- In 1872, at age 16, Booker left home and walked 500 miles to Hampton Normal Agricultural Institute in Virginia. Along the way he took odd jobs to support himself. He convinced administrators to let him attend the school and took a job as a janitor to help pay his tuition, and he saved as much as he could from his previous work.

- General Samuel C. Armstrong, a white man, discovered young Booker and recognized his intellect, offered him a scholarship.

- Armstrong was a commander of a Union African-American regiment during the Civil War and was a strong supporter of providing newly freed slaves with a practical education. Armstrong became Washington’s mentor, strengthening his values of hard work and strong moral character.

- Booker T. Washington graduated from Hampton in 1875 with high marks, and for a time he went back to his old grade school to teach, and attended a religious school for a year in Washington D.C.

- Several years later, in 1879, Booker was chosen to speak at Hampton’s graduating ceremonies, and was offered a job to teach there.

- Two years later, the Alabama state legislature approved for $2000 to be spent to create a “colored” school named the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. General Armstrong, Booker’s mentor, recommended him to run the school. He was offered the job and gladly accepted.

- Fact: the school still exists! It’s now known as Tuskeegee University.

- Classes were first held in an old church, while Washington traveled all over the countryside promoting the school and raising money. He reassured whites that nothing in the Tuskegee program would threaten white supremacy or pose any economic competition to whites.

- Two years later, the Alabama state legislature approved for $2000 to be spent to create a “colored” school named the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. General Armstrong, Booker’s mentor, recommended him to run the school. He was offered the job and gladly accepted.

- Under Booker T. Washington’s leadership, Tuskegee became a leading school in the country. At his death, it had more than 100 well-equipped buildings, 1,500 students, a 200-member faculty teaching 38 trades and professions, and a nearly $2 million endowment.

- Washington put much of himself into the school’s curriculum, stressing the virtues of patience, enterprise, and thrift.

- He believed that if African Americans worked hard and obtained financial independence and cultural advancement, they would eventually win acceptance and respect from the white community.

The Atlanta Compromise

- In 1895, Booker T. Washington publicly presented his philosophy on race relations in a speech at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia, known as the “Atlanta Compromise.”

- In his speech, Washington stated that African Americans should accept disenfranchisement and social segregation as long as whites allow them economic progress, educational opportunity and justice in the courts. This started a firestorm in parts of the African-American community, especially in the North.

- Activists deplored Washington’s conciliatory philosophy and his belief that African Americans were only suited to vocational training.

- While Washington did much to help advance many African Americans, there was some truth in the criticism to his approach to improving race relations with white Americans.

- African Americans were completely excluded from the vote and political participation through black codes and Jim Crow laws as segregation and discrimination became institutionalized throughout the South and much of the United States.

- Activists deplored Washington’s conciliatory philosophy and his belief that African Americans were only suited to vocational training.

- In his speech, Washington stated that African Americans should accept disenfranchisement and social segregation as long as whites allow them economic progress, educational opportunity and justice in the courts. This started a firestorm in parts of the African-American community, especially in the North.

Booker T. Washington: Presidential Advisor & Legacy

- In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington—age 45, to the White House, making him the first African American to be so honored.

- President William Howard Taft, used Washington as an adviser on racial matters, partly because he accepted racial subservience.

- His White House visit and the publication of his autobiography, Up from Slavery, brought him both acclaim and indignation from many Americans. While some African Americans looked upon Washington as a hero, others, including many African-Americans, saw him as a traitor.

- Booker T. Washington was a complex individual. On one hand, he was openly supportive of African Americans taking a “back seat” to whites, while on the other he secretly financed several court cases challenging segregation.

- By 1913, Washington had lost much of his influence. The newly inaugurated Wilson administration was cool to the idea of racial integration and African-American equality.

- Booker T. Washington remained the head of Tuskegee Institute until his death on November 14, 1915, at the age of 59, of congestive heart failure.

Famous Quotes

- “Success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has overcome.”

- “Character, not circumstances, makes the man.”

- “Excellence is to do a common thing in an uncommon way.”

Thomas D’Arcy McGee, better known to Canadians as simply D’Arcy McGee, was a politician, journalist, poet, and historian who actually spent the majority of his life outside of Canada. He is known as one of the most eloquent Fathers of Confederation, and has since then gained notoriety for being one of the few Canadian politicians to ever be assassinated (on Sparks Street!).

Thomas D’Arcy McGee, better known to Canadians as simply D’Arcy McGee, was a politician, journalist, poet, and historian who actually spent the majority of his life outside of Canada. He is known as one of the most eloquent Fathers of Confederation, and has since then gained notoriety for being one of the few Canadian politicians to ever be assassinated (on Sparks Street!).

D’Arcy McGee emigrated from Ireland to the US in 1842 when he was 17 years old. Two years later, he became the editor of the Boston Pilot newspaper while living in Massachusetts. In 1845, only a year after becoming the editor of the Boston Pilot, he returned to Ireland to edit the newspaper Nation, known for its nationalist (support of Irish independence from Great Britain) sentiment at a time when much of Ireland was bitterly divided about British rule. In 1848 he participated in a failed nationalist uprising in Ireland, and fled back to the US fearing for his safety.

For nearly 10 years after this event, McGee went back to editing newspapers. Throughout this time he was preoccupied with the plight of hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrants, and became increasingly discouraged by the lack of support for his initiatives in the US. He moved to Montreal in 1857 at the request of the Irish community there that took interest in his work, and he began another newspaper called New Era, which advocated for a “new nationality” for Canada, federated geographically, and freer from British interventions. He likewise called for nation-building initiatives like the construction of a transcontinental railway, settling the West, and more protectionist economic policies.

Thomas D’Arcy McGee was elected in Montreal to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada in 1858 when he was 33 years old. He was a member of George Brown’s Reform Party but broke off from them when they did not support his vision of national projects, and joined the much more supportive John A. Macdonald’s “Great Coalition” leading up to Confederation. By 1866, many Irish voters felt he was more concerned with Canadian affairs than Irish ones, and Macdonald dropped him from Cabinet due to his unpopularity with his former supporters.

While McGee always sought for Irish independence from Britain, he was opposed to the Fenian movement in North America which planned to obtain Irish independence from Britain by violent revolution at home and by conquering Canada and holding it essentially for ransom.

Only a year after D’Arcy McGee played a prominent role in the founding of Canada, he was assassinated in the early morning hours on Sparks Street on Tuesday, April 7th, 1868. Within 24 hours Ottawa police arrested Irish nationalist Patrick James Whelan at a local hotel following a tip from the public. Searching through his belongings, they found numerous references to revolutionary-Irish ties and a revolver allegedly fired the previous day.

A trial began and despite the seemingly insurmountable evidence against Whelan, his defence lawyer poked many holes in the prosecution’s case. Despite demonstrating numerous instances that raised reasonable doubt as to Patrick James Whelan’s guilt, circumstantial evidence proved strong enough to find him guilty and he was sentenced to death. Up until his execution, Whelan strongly maintained his innocence, making D’Arcy McGee’s assassination the “greatest murder mystery in Canadian political history.” At present, it is still unknown who definitively assassinated McGee a week before his 43rd birthday, and it is highly encouraged that the reader look into some of the more interesting theories surrounding his death.

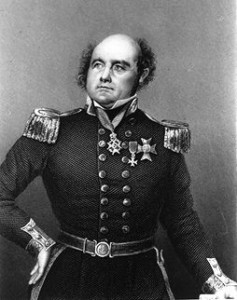

David Thompson (1770-1857)

David Thompson, explorer, cartographer (born 30 April 1770 in London, England; died 10 February 1857 in Longueuil, Canada East). David Thomson was called “the greatest land geographer who ever lived.” He walked or paddled 80,000 km or more in his life, mapping most of western Canada, parts of the east and the northwestern United States. And like so many geniuses, his achievements were only recognized after his death.

Early Life

Thompson attended the Grey Coat Hospital in London, a school for the poor and orphaned. He was recruited by the Hudson’s Bay Company when he was 14 and in 1784 he sailed to what is now Churchill, Manitoba, to work as an apprentice in the fur-trading business.

In that northern wilderness Thompson had a remarkable experience that changed him forever. In his journal, he describes how the devil came into his room and started playing checkers with him. “I was sitting at a small table with the chequer board before me, when the devil sat down opposite to me, his features and colour were those of a Spaniard, he had two short black horns on his forehead which pointed forwards; his head and body down to his waist (I saw no more) was covered with glossy black curling hair…” They played and the devil lost every game. “He got up or rather disappeared. My eyes were open it was broad daylight, I looked around, all was silence and solitude, was it a dream or was it reality? I could not decide.”

Whichever it was, the experience changed him. He remained a devout Christian throughout his life.

Travels and Encounter with Aboriginal Peoples

When he was 17, Thompson left Churchill to walk and paddle across the prairies to the Alberta foothills where thousands of Peigan Aboriginal people were camped. He spent a magical winter in the tent of an 80-year-old elder named Saukamappee, who told him stories about the Plains Aboriginal peoples as the fire burned to keep them warm. Saukamappee described the Peigans’ encounter with smallpox, which killed hundreds. The Peigans had planned a nighttime raid on an enemy band, but arrived to find them all dead. It turned out to be smallpox, and when they took the possessions of the dead, they too became infected. “We had no belief that one man could give it to another, any more than a wounded man could give his wound to another,” Saukamappee said. “We shall never be again the same people.”

Thompson learned to speak several Aboriginal languages and was an acute and sympathetic observer at a time when most Europeans still saw Aboriginal people as savages.

Map-Making and Exploration

Thompson learned astronomy and mathematics and spent so much time examining the sun and stars that he lost his sight in one eye. He broke his leg and it healed badly and he had a limp for the rest of his life. Yet this one-eyed, limping man mapped more territory than any other European. He surveyed the territory west of Lake Superior and the 49th parallel, which eventually became the dividing line between Canada and the United States. He mapped the north and paddled to the west coast. He mapped not only the land but also the cultural and religious practices of its inhabitants. His journals (which numbered hundreds of pages) and his maps provided the most complete record of a territory that was more than 3.9 million square km and contained dozens of different First Nations bands.

In 1799, Thompson married a Métis woman named Charlotte Small. He was 29; she was 13. It was a love affair that lasted 58 years. They had 13 children, 5 of them while he was still exploring. Thompson often took those children and his wife on his trips, venturing into unknown, sometimes hostile territory. At the Hudson’s Bay Company, he was valued as a fur trader, but Thompson wanted to explore rather than trade. He left the HBC and joined the rival North West Company where he spent the next 15 years exploring. In all, he spent 27 years mapping the west. “The age of guessing is passed away,” he wrote. Thompson predicted the changes that would come to the west, that it would become farmland and Aboriginal peoples would be pushed from their land. As the one who mapped it, he was aware that he was contributing to that future.

Later Years

Thompson’s later years were marred by tragedy. He moved to Montréal in 1812 so his children could get a formal education. He had saved some money from his years as a trader but lost most of it in bad investments in Montréal. Personal tragedy followed his financial setbacks. His five-year-old son John died, and then his seven-year-old daughter. His eldest son rebelled and left home and Thompson never saw him again.

He took on odd jobs to pay the rent and kept working on the maps he had drawn of the west. But he couldn’t find a publisher for the maps. In the end he sold them to Arrowsmith, a London publisher, who paid him 150 pounds, an absurdly low sum for his life’s work. Then Arrowsmith didn’t publish them under Thompson’s name, which would have earned him some measure of fame, at least as a map-maker. Instead they used his maps to correct their own and didn’t credit Thompson.

He took on the job of surveying the vast estate of fellow explorer Alexander Mackenzie, who wasn’t as ambitious or accomplished as Thompson, but was a much better manager of money. When that job ended, Thompson had trouble finding work and had to pawn his surveying tools and his winter coat.

He moved in with his daughter and son-in-law and spent his time working on his journals, trying to make them into something publishable. His one good eye began to fail him and he never completed the manuscript. One of the greatest explorers in history died in poverty and obscurity in 1857 and was buried in Montréal. His wife Charlotte was inconsolable, and she died less than three months later.

Legacy

The land mass mapped by Thompson amounted to 3.9 million square kilometres of wilderness, or one-fifth of all of North America. His contemporary, the great explorer Alexander Mackenzie, remarked that Thompson did more in ten months than he would have thought possible in two years.

Charles-Michel d’Irumberry de Salaberry was a French British Army and Canadian militia officer who is known for his role in the War of 1812. Born in the Province of Quebec De Salaberry felt the call to arms early in life, volunteering to enlist in the British military at 14 years old. Two years later, in 1794 he became an ensign (now considered Second Lieutenant).

Charles-Michel d’Irumberry de Salaberry was a French British Army and Canadian militia officer who is known for his role in the War of 1812. Born in the Province of Quebec De Salaberry felt the call to arms early in life, volunteering to enlist in the British military at 14 years old. Two years later, in 1794 he became an ensign (now considered Second Lieutenant).

De Salaberry served admirably in British colonies such as St. Domingo, Guadaloupe, and Martinique before his first posting to Lower Canada. He did not stay in Canada for long on his first posting, and was sent to the West Indies in 1797, when he was 19 years old. In 1799, at 21 years old, de Salaberry was promoted to Captain, and by 25 years old he received command of a company of the 1st Battalion in the 60th Foot. Three years later, in 1806, de Salaberry was transferred to the 5t Battalion of the 60th Foot, which was commanded by Francis de Rottenburg, considered a revolutionary in light infantry and rifle tactics. Evidently de Salaberry earned the trust of de Rottenburg, because he was entrusted with recruiting new soldiers between 1806 and 1807.

Having earned the confidence and trust of Francis de Rottenburg throughout his time in the West Indies, de Rottenburg requested to bring de Salaberry with him to serve as his aide when he was posted to Lower Canada in 1810, when he was 32 years old.

In Canada, de Salaberry is perhaps best known for proposing, raising, training, and commanding Quebec’s provincial military corps, the Canadian Voltigeurs. In 1811, de Salaberry became a major and in 1812, when war with the United States seemed both inevitable and imminent, he proposed the formation of the Voltigeurs and set about using his recruiting talents to find good soldiers. He began recruiting in April 1812 and by the autumn de Salaberry was commanding the Voltigeurs as they went to the frontier of Lower Canada to lead efforts in defending the border. From November 1812 to the Fall of 1813, de Salaberry successfully repelled several American attacks at the Canadian border.

In the fall of 1813, the Americans launched a major offensive against Montreal, which would prove to be a defining event in de Salaberry’s career. He was stationed with the Voltigeurs on the Canadian side of the Châteauguay River when the Americans sent a 3700-man division to invade Canada from the American side of the river, just south of the border between Quebec and New York State. De Salaberry’s Voltigeurs were outmatched, with a ragtag mixture of 1800 regular soldiers, provincial troops, and untrained & untested militia soldiers, the majority of whom were Quebecois along with a contingent of First Nations warriors. However, de Salaberry’s advantage was being familiar with the area he was defending, and he was successfully able to use his familiarity with the terrain to ambush the Americans as they attempted to cross the border into Canada. It did not take long for the Americans to retreat, and de Salaberry’s prowess was responsible for thwarting a major American offensive in the War of 1812.

He did not see any other action in the War of 1812 and relinquished command of the Voltigeurs two years later, in 1814. He left the army a year later and settled near Chambly, Quebec, where he became a wealthy businessman and landowner. He received an Army Gold Medal for the battle at Châteauguay and was made a companion of the Order of the Bath. Following his retirement from the military de Salaberry became a folk hero in French Canada for rescuing Montreal from an uncertain fate. In 1818 he made a foray into politics, becoming a legislative councillor for Lower Canada.

Without question, de Salaberry’s legacy is hinged upon creating Quebec’s provincial military force, the Canadian Voltigeurs, and for his efforts in repelling American forces seeking to conquer Montreal in the War of 1812.

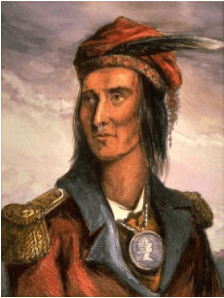

Haiwatha

Hiawatha is an important figure in the precolonial history of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) of present-day southern Ontario and upper New York (ca. 1400–1500s) – we are unsure of the exact time period…

Hiawatha is an important figure in the precolonial history of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) of present-day southern Ontario and upper New York (ca. 1400–1500s) – we are unsure of the exact time period…

Major contributions to Canadian history:

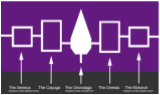

-The Hiawatha character will recount the legend & story of the three prominent figures who brought together the Confederacy of the five nations (Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, Mohawk, and Seneca), also called The Iroquois League or Great Law of Peace.

Deganawida: The Great Peacemaker

- An outsider, taught the laws of peace

- Helped to heal Haiwatha’s grief through the Ceremony of Condolence*

- Unified the Five nations (Iroquois League)

Haiwatha: Onondaga Warrior

- Wanderer

- Self-exiled, following the loss of his wife and children due to blood feuds

- Disciple of Deganawida

Atotarho: Onondaga War Chieftain

- Aggressor

- Possessor of powerful dark magic

Important terms and definitions:

- Ceremony of Condolence: Led by Deganawida, this ceremony enabled Haiwatha to heal after the loss of his wife and daughters

- “Wampum”: Belt; purple and white beads made from shells. Conveys the unity of the five nations. Hiawatha created a wampum and wore it around his neck to remember the ritual of the ceremony.

Bound on strings, wampum (139kb/1sec) beads were used to create intricate patterns on belts. These belts are used as a guide to narrate Haudenosaunee history, traditions and laws, The origins of wampum beads can be traced to Aiionwatha, commonly known as Hiawatha at the founding of the League of Five Nations. Archeological study however, has found it to have been used long before the union of the nations.

Most commonly made from the Quahog, a round clam shell, the word wampum comes from the Algonquin term for the shells. While it is called Ote-ko-a in the Seneca (198kb/2sec) language, wampum is the most widely recognized term. For the Haudenosaunee, wampum held a more sacred use.

Wampum served as a person’s credentials or a certificate of authority. It was used for official purposes and religious ceremonies and in the case of the joining of the League of Nations was used as a way to bind peace.

Wampum served as a person’s credentials or a certificate of authority. It was used for official purposes and religious ceremonies and in the case of the joining of the League of Nations was used as a way to bind peace.

Source: HAUDENOSAUNEE CONFEDERACY:

http://www.haudenosauneeconfederacy.com/wampum.html

- Most prevalent translations of the name Hiawatha:

He who combs & He who has lost his mind, but seeks to find it

**He who combs meaning: Atotarho was persuaded to join — possibly by the combined force of the followers and/or the offer of a leadership role in the new confederacy. Hiawatha combed the snakes out of Atotarho’s hair.

- Chief sachem: Great Chief

- Haudenosaunee: Iroquois

VIDEO LINK (FOR A GENERAL IDEA OF THE HISTORY):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=79RApCgwZFw

Harriet Tubman was born into slavery as Araminta Ross (nicknamed Minty) in 1820, Maryland, and spent her childhood working for her owners as an unpaid slave. Preferring working in the fields to servitude in the home, she learned to follow directions based on geographic details as well as how to use herbs and plants found outdoors for therapeutic and medicinal purposes—skills that proved to be invaluable when she fled to secure her own freedom, and as the ‘conductor’ of the Underground Railroad.

Harriet Tubman was born into slavery as Araminta Ross (nicknamed Minty) in 1820, Maryland, and spent her childhood working for her owners as an unpaid slave. Preferring working in the fields to servitude in the home, she learned to follow directions based on geographic details as well as how to use herbs and plants found outdoors for therapeutic and medicinal purposes—skills that proved to be invaluable when she fled to secure her own freedom, and as the ‘conductor’ of the Underground Railroad.

It is important to note that the Underground Railroad was not an actual railroad, but was rather a term that began to be used in the 1830s (when railway technology came about) to describe a secretive network of people and safehouses across America that helped slaves reach freedom in the North, and particularly in Canada following the 1850 passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in the US, which allowed slave catchers to pursue escaped slaves into free Northern states. In 1793 Canada passed the Act to Limit Slavery, in which a provision was added that any enslaved person who reached Upper Canada became free as soon as they arrived.

When Tubman was 14 she witnessed a young black man attempting to escape to freedom. As she watched she was struck in the head by a large weight that the slave owner attempted to throw at his escaping slave, suffering a serious head injury that caused her to suffer from seizures, hallucinations and sleep disturbances for the rest of her life.

In 1844, when she was 24, Harriet married a free Black man named John Tubman while she was still a slave, which meant that her marriage was not legally recognized. She tried to convince him to flee north to freedom with her, but he refused.

In 1849, when Tubman was 29, her owners died and she feared being resold into slavery to cover their debts, so she fled north alone, and made her way to Philadelphia with assistance from groups of Quakers who were involved in the Underground Railroad. Tubman stayed in Philadelphia and worked for a year, raising enough money to rescue her niece and two daughters from Maryland before they were auctioned off to another slave owner. She returned to Maryland to personally assist her family’s escape, thus beginning her life as a ‘conductor’ of the Underground Railroad.

Following this extremely personal mission, she began to meet other prominent abolitionists who were part of the Underground Railroad and assisted her with getting freed slaves to Philadelphia by providing food, clothing, shelter, and financial assistance along the way. When the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850, Tubman—a fugitive slave herself—moved to St. Catherines, Canada West in 1851, and altered the Underground Railroad escape route to this location.

After moving to St. Catherines in December 1851, Harriet Tubman was quickly able to find work and rent a house. She lived with her family and continually opened her doors to newly arrived freed slaves offering food and clothing to those who needed it while supporting many charitable endeavours in the town. Throughout this time she continued leading missions to free former slaves in the US, forging routes through swamps, forests, and other difficult terrain through many states, always using the North Star for guidance (she always travelled by night). In total she made at least 10 trips and transported at least 70 people to Canada using these trails. She was never caught and never lost a passenger.

Following two harsh winters, in 1959 Harriet Tubman moved with her parents and brother to Auburn, New York, in order to avoid the harsh Canadian climate. Tubman gave lectures at anti-slavery gatherings and used them to support both her family and the abolition movement, and became increasingly involved in the women’s rights movement as well. In 1862, after the Civil War broke out, and at 42 years of age, Harriet Tubman enlisted in the Union Army, combatting slavery by assisting the Union as a nurse, spy, scout, laundress, and cook until 1864. She returned to Auburn after the Civil War where she remarried, adopted a young girl, and opened a nursing home for elderly African Americans to be cared for with dignity.

In recognition of Harriet Tubman’s courage, devotion to humanitarian efforts, heroism and life of service, March 10 was declared Harriet Tubman Day in the US and St. Catherines, and in 2005 she was designated a “Person of National Significance” by the Government of Canada.

James Austin (1813-1897)

James Austin was born on March 6th, 1813, in Tandragee, Northern Ireland. He came to Canada with his parents when he was 16 years old in 1829.

James Austin was born on March 6th, 1813, in Tandragee, Northern Ireland. He came to Canada with his parents when he was 16 years old in 1829.

His family moved to Toronto, and he became an apprentice to William Lyon Mackenzie, the 1st Mayor of Toronto and a leader during the 1837 Upper Canada Rebellion.

While not directly involved in the rebellion against the corrupt and repressive British colonial government in present-day Ontario, his connection with William Lyon Mackenzie forced him to flee to the United States for several years.

In 1843, at 30 years old, Austin returned to Toronto when those involved in the Upper Canada Rebellion were pardoned.

In 1844, at 31, James Austin married Susan Bright, and together they had five children. Unfortunately, his two eldest boys died at ages 13 and 38, respectively. In 1866, he build the famous Spadina House for his family, which is now a popular Toronto museum.

He entered the business world shortly after and founded Austin & Foy Wholesale Company (a grocery store) with his business partner Patrick Foy. The company was successful for a number of years, but Austin was interested in doing other things, and in 1870, at the age of 57, Austin and Foy dissolved their company, leaving Austin with modest wealth.

From then on, James Austin became a successful player in the Toronto financial world. The year after his company dissolved, Austin founded The Dominion Bank, which would eventually become today’s Toronto-Dominion Bank (or TD Bank for short).

He soon suggested that, in addition to its main office on King Street East, there should be a branch nearer the residential quarter, mainly for the convenience of savings depositors. This was located on Queen Street West. Other chartered banks soon followed this innovative practice of operating multiple branches in larger urban centres.

Austin was the president of The Dominion Bank until he died at the age of 84 in 1897. During his time as president of The Dominion Bank, James Austin became involved in a number of other prominent institutions, such as the Queen City and Hand-to-Hand insurance companies, the North Scotland Canadian Mortgage company, and the Consumers’ Gas Company.

He retained all of his positions up until his death, despite suffering from deafness late in life. He died after several months of illness at the age of eighty-four. At his death he had a fortune of some $300,000 which was divided between his son and daughter. His business interests and his home passed on to his surviving son Albert William Austin.

John Newton (1725-1807)

Early Life

Early Life

- John Newton was born in Wapping, London, in 1725. He was the son of Elizabeth and John Newton Sr, who was a ship captain that worked primarily in the Caribbean.

- John’s mother Elizabeth died of tuberculosis in 1732, just two weeks before young John’s seventh birthday. John’s father then sent him to boarding school for two years while he was working at sea, then moved to Essex County to live with his father’s new wife.

- When he was 11 years old, John’s father took him out to sea on a voyage with him, and he sailed a total of six voyages with his father before he retired in 1742.

- Following his retirement John’s father was planning to have his son work on a sugarcane plantation in Jamaica, but he had other plans. At age 17 he signed up to join the merchant marine, and set sail to the Mediterranean Sea.

Life at Sea

- In 1743, while going to visit friends, Newton was captured and “pressed” into the naval service by the Royal Navy. He became a midshipman aboard HMS Harwich.

- Impressment is the act of taking men into a military or naval force by compulsion, with or without notice.

- At one point Newton tried to desert and was punished in front of the crew of 350. Stripped to the waist and tied to the grating, he received a flogging of eight dozen lashes!

- Later, while traveling to India, he transferred to Pegasus, a slave ship bound for West Africa. The ship carried goods to Africa and traded them for slaves to be shipped to the colonies in the Caribbean and North America.

Abandonment, Enslavement, and Eventual Rescue

- Just like on the HMS Harwich, Newton did not get along with the crew of Pegasus. They abandoned him in West Afirca with a slave dealer who owned a lemon tree plantation on an island just off the coast.

- John Newton was ‘given’ to the wife of the slave dealer, where he was abused and treated as poorly as many of her African slaves.

- Newton later recounted this period as the time he was “once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in West Africa.”

- John’s father, John Newton Sr. grew increasingly worried about his son, and in 1748 he asked the captain of the Greyhound, a British trading vessel, to find his son, and successfully bargained for his return to England aboard the Greyhound.

Conversion to Evangelical Christianity

- During the 1748 voyage to England after his rescue, Newton had a spiritual conversion. The ship hit a severe storm off the coast of Ireland and almost sank. Newton awoke in the middle of the night and, as the ship filled with water, called out to God. The cargo shifted and stopped up the hole, and the ship drifted to safety. Newton marked this experience as the beginning of his conversion to evangelical Christianity.

- Following this incident Newton began to read the Bible and other religious literature. By the time he reached Britain on March 10, 1748, he considered himself a convert to Evangelical Christianity

- John Newton marked the day of this anniversary for the rest of his life. From that point on, he avoided profanity, gambling, and drinking.

- Newton gained sympathy for the slaves during his time in Africa.

Return to England and work in the slave trade

- Upon his return to England by way of Liverpool, Newton’s father helped arrange for him to be a first mate aboard a slave ship named Brownlow, which sailed from Guinea to the Caribbean.

- While in West Africa, Newton became ill with a fever and professed his full belief in God, asking Him to take control of his destiny. He later said that this was the first time he felt totally at peace with God.

- After his return to England in 1750, Newton made three voyages as captain of the slave ships Duke of Argyle (1750) and African (1752–53 and 1753–54).

- After suffering a severe stroke in 1754, he gave up sailing and actively participating in the slave trade, but continued investing his money in slaving operations.

Post-Slave Trade

- In 1750, at age 25, Newton married his childhood sweetheart, Mary Catlett, and adopted two of his orphaned nieces.

- In 1755 at age 30, Newton was appointed a tax collector at the Port of Liverpool and studied ancient languages and religious texts in his spare time.

- In 1757 he applied to be an ordained Anglican priest, but he would not be ordained until 1764. He worked for 16 years as a priest in the community of Olney, where he became well-known for his community work.

- In 1767 William Cowper, the poet, moved to Olney. He collaborated with the priest on a volume of hymns; it was published as Olney Hymns in 1779, and contained the famous hymn still sung today; “Amazing Grace!”

- In 1779, he became a priest in London and was considered a very popular preacher.

- John Newton even provided spiritual guidance to William Wilberforce, a British MP who played a very prominent role in the abolition of slavery. He’s also a character in the show!

- In 1788, 34 years after he had retired from the slave trade, Newton broke a long silence on the subject with the publication of a forceful pamphlet ‘Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade’, in which he described his experience with the horrific conditions of the slave ships.

- He apologized for “a confession, which … comes too late … It will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me, that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders.” He had copies sent to every MP, and the pamphlet sold so well that it needed to be re-printed multiple times!

- Newton became an ally and mentor to William Wilberforce, leader of the Parliamentary campaign to abolish the African slave trade. He lived to see the British passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807, which abolished the slave trade in England. He died shortly thereafter.

Famous Quotes

- “Amazing grace! How sweet the sound. That saved a wretch like me! I once was lost but now am found, Was blind but now I see.”

- “I am not what I ought to be, I am not what I want to be, I am not what I hope to be in another world; but still I am not what I once used to be, and by the grace of God I am what I am”

- “We judge things by their present appearances, but the Lord sees them in their consequences.”

Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes (1902-1967) was an American poet, social activist, playwright, and columnist who gained prominence during his time living in Harlem, New York.

Langston Hughes (1902-1967) was an American poet, social activist, playwright, and columnist who gained prominence during his time living in Harlem, New York.

Early Life

- Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri in 1902, and grew up mainly in Lawrence, Kansas.

- Hughes’ parents, James Hughes and Carrie Langston, separated soon after his birth and his father moved to Mexico. The Langston family name was made famous by his grandfather Charles and Charles’ brother John, two of the most prominent African-American abolitionists during the mid to late 1800s.

- While Hughes’s mother moved around during his youth, Hughes was raised in Kansas by his maternal grandmother, Mary, until she died in his early teens. From that point, he went to live with his mother, and they moved to several cities before eventually settling in Cleveland, Ohio.

- Through the black American oral tradition and drawing from the activist experiences of her generation, Mary Langston instilled in her grandson a lasting sense of racial pride.

- During high school in Cleveland, Hughes’ writing talent was recognized by his high school teachers and classmates. Hughes had his first pieces of verse published in the Central High Monthly, a sophisticated school magazine. Soon he was on the staff of the Monthly, and publishing in the magazine regularly.

- Hughes graduated from high school in 1920 and spent the following year in Mexico with his father. Around this time, Hughes’s poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” was published in ‘The Crisis’ magazine (created by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People NAACP) and was highly praised.

Enrollment at Columbia University and Formative Years

- In 1921 Langston Hughes enrolled at Columbia University in engineering—a compromise he reached with his father for his tuition to be paid for.

- During this time, Hughes became immersed in a growing, unique African-American cultural movement in the neighbourhood of Harlem, New York, known as the Harlem Renaissance.

- Hughes dropped out of Columbia in 1922 because of the racial prejudice he experienced there.

- Hughes quickly became an integral part of the arts scene in Harlem, so much so that in many ways he defined the spirit of the age, from a literary point of view. The Big Sea, the first volume of his autobiography, provides such a crucial first-person account of the era and its key players that much of what we know about the Harlem Renaissance we know from Langston Hughes’s point of view.

- Hughes began regularly publishing his work in ‘The Crisis’ and Opportunity magazines, and in doing so, he got to know other writers of the time.

- When his poem “The Weary Blues” won first prize in the poetry section of the 1925 Opportunity magazine literary contest, Hughes’s literary career was launched. His first volume of poetry, also titled The Weary Blues, appeared in 1926.

- At this point in Langston Hughes’s evolution as a poet, he began to use the rhythm of African American music, particularly blues and jazz. This set his poetry apart from that of other writers, and it allowed him to experiment with a very rhythmic free verse.

1926: Langston Hughes enrols in Lincoln University in Pennsylvania

- Langston Hughes enrolled in the historically black Lincoln University in Pennsylvania in 1926. He was supported by a patron of the arts, a wealthy white woman in her seventies named Charlotte Osgood Mason.

- Mason directed Hughes’s literary career, convincing him to write his debut novel Not Without Laughter, which was published in 1930. The protagonist of the story is a boy named Sandy, whose family must deal with a variety of struggles due to their race and class, and having to relate to one another.

- Hughes and Mason had a falling out shortly after Not Without Laughter was published, and their relationship came to an end. Hughes sank into a period of intense personal unhappiness and disillusionment.

- After Hughes earned a B.A. degree from Lincoln University in 1929.

- Mason directed Hughes’s literary career, convincing him to write his debut novel Not Without Laughter, which was published in 1930. The protagonist of the story is a boy named Sandy, whose family must deal with a variety of struggles due to their race and class, and having to relate to one another.

Post 1930, WWII, and beyond

- Following the publishing of Not Without Laugher, Hughes began to develop his interest in socialism. In 1932 he sailed to the Soviet Union with a group of young African Americans, but never considered himself a communist—he preferred the ideals of socialism much more than he did segregated America.

- Later in the 1930s, Hughes’s primary writing was for the theatre. His drama about mixed-race relationships and the South – “Mulatto” – became the longest running Broadway play written by an African American until Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun” (1958).

- In 1942, during World War II, Hughes began writing a column for the African American newspaper, the Chicago Defender.

- In 1943 he introduced the character of Jesse B. Semple, or Simple, to his readers. This fictional everyman, while humorous, also allowed Hughes to discuss very serious racial issues. The Simple columns were very popular– they ran for twenty years and were collected in several books.

- Money was a nagging concern for Hughes throughout his life. While he managed to support himself as a writer, he was never financially secure. However, in 1947 through his work writing the lyrics for the Broadway musical “Street Scene,” Hughes was able to earn enough money to purchase a house in Harlem, which had been his dream.

Legacy & Death

- Langston Hughes was deemed the “Poet Laureate of the Negro Race” in his later years, a title he encouraged. Hughes meant to represent the race in his writing and he was, perhaps, the most original of all African American poets. On May 22, 1967 Langston Hughes died after complications from abdominal surgery to remove a tumor. Hughes’ funeral, like his poetry, was all blues and jazz: Very little was said by way of eulogy, but the jazz and the blues being played at the funeral were ‘hot’, and the final tribute to this writer so influenced by African American musical forms was fitting.

Famous Quotes

- In his 1940 autobiography The Big Sea he wrote: “I was unhappy for a long time, and very lonesome, living with my grandmother. Then it was that books began to happen to me, and I began to believe in nothing but books and the wonderful world in books — where if people suffered, they suffered in beautiful language, not in monosyllables, as we did in Kansas.

- “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too.”

Laura Secord was born as Laura Ingersoll in 1775, and her father Thomas Ingersoll was an American who sided with the “Patriots” who were loyal to the British Crown during the American Revolution that took place from 1775-1783. Thomas moved his family to the now-Canadian side of the Niagara Peninsula region in 1795 because he was a Loyalist and wished to live among fellow devotees to the British Crown and Empire. He ran a tavern in Queenston, Ontario and the site of his farm is today the town of Ingersoll, Ontario.

Laura Secord was born as Laura Ingersoll in 1775, and her father Thomas Ingersoll was an American who sided with the “Patriots” who were loyal to the British Crown during the American Revolution that took place from 1775-1783. Thomas moved his family to the now-Canadian side of the Niagara Peninsula region in 1795 because he was a Loyalist and wished to live among fellow devotees to the British Crown and Empire. He ran a tavern in Queenston, Ontario and the site of his farm is today the town of Ingersoll, Ontario.

Laura Secord is best known for her role in the War of 1812. During this war, Laura Secord walked 30km from Queenston, Ontario (5km north of Niagara Falls) to Beaver Dams to inform British Loyalist soldier James FitzGibbon that American forces were planning an attack on his outpost. The story of her 30km journey has become something of a Canadian legend, and she has become a mythical figure in Canadian history. In 1797, when she was 22, Laura Ingersoll married James Secord, who was a merchant in Queenston.

Her husband James was wounded at the Battle of Queenston Heights, early in the War of 1812, when American forces occupied Queenston where Laura and James called home. Laura Secord rescued her wounded husband from the battlefield and took him home to nurse him back to good health. In June 1813 James Secord was still recuperating when occupying American forces forced them to billet some American officers at their home. During their stay, Laura Secord overheard the officers planning an attack on British forces at Beaver Dams.

With her husband incapacitated, Laura Secord set off on her own to warn the British outpost at Beaver Dams, taking a divergent route through treacherous terrain to avoid American sentries. She received assistance by a group of First Nations men she encountered along the way who were sympathetic to her plight and guided her to her destination. She reached British Loyalist and soldier James FitzGibbons on either the 22nd or 23rd of June.

On June 24th, after having been alerted to the American assault plans by Laura Secord, 300 Caughnawaga, 100 Mohawk warriors—both aligned with the British—and 50 British soldiers led by FitzGibbons ambushed the American troops and prevented their surprise assault of Beaver Dams. No mention of Laura Secord was made in the official British reports of the victory.

While details of Laura Secord’s 30km journey are uncertain, her story has become part of the Canadian national identity, and has been mythologized in Canadian popular culture. Revered Historian Pierre Berton stated that Secord’s story has been “used to underline the growing myth that the War of 1812 was won by true-blue Canadians.”

Laura Secord herself never revealed how exactly she became aware of the American plan, and while she did absolutely make the 30km trek to deliver a message to James FitzGibbon in Beaver Dams, it is unknown if she got there before Aboriginal scouts arrived with the same message. FitzGibbon later testified in support of Laura Secord’s petition to the government for a pension that she did indeed warn him of a planned American attack and positioned the Aboriginal forces supporting Beaver Dams accordingly.

Her petition for a military pension refused, Secord only gained recognition later in life when in 1860, the future Edward VII, then the Prince of Wales read a letter she wrote to him of her efforts that was packaged among other letters from War of 1812 veterans. Upon returning to England, he personally sent her an award of 100 pounds. She died in 1868 at 93 years of age. The chocolate company was named after her in 1913 because she was “an icon of courage, devotion, and loyalty.”

Frederick Arthur Stanley was born in January 1841 and was known simply as Frederick Stanley until 1886, and Lord Stanley of Preston between 1886 and 1893. He was a Conservative Party politician in the United Kingdom and served as the Colonial Secretary (Minister for the Colonies) from 1885-1886.

Frederick Arthur Stanley was born in January 1841 and was known simply as Frederick Stanley until 1886, and Lord Stanley of Preston between 1886 and 1893. He was a Conservative Party politician in the United Kingdom and served as the Colonial Secretary (Minister for the Colonies) from 1885-1886.

Lord Stanley’s experience with and knowledge of the British colonies led to his appointment as the sixth Governor General of Canada, a position that he served from 1888 to 1893. Despite being publicly very shy, he was a strong advocate for closer ties between Great Britain and its dominions and was known for his care and discretion when handling political situations. During his time as Governor General of Canada he travelled frequently across the country, and came to appreciate the untamed beauty of the West.

Lord Stanley developed a close personal friendship with Sir John A. Macdonald, and when he died in office in 1891, Lord Stanley was reportedly quite distraught by the loss. Lord Stanley additionally cemented the status of Governor General as non-political and non-partisan when he refused to agree to a controversial motion that would reverse legislation passed by the Quebec government.

He was an avid sportsman and his family is well known for its athletic activity and support of the sporting community.

Most notably, Lord Stanley is remembered as an important figure in Canadian history because in 1893 he donated a trophy that was intended to determine the Canadian hockey champion in a fair and open manner. The Stanley Cup is the oldest trophy competed for by professional athletes in North America, and is arguably the greatest in terms of its design and significance to the sport.

The Stanley cup was first awarded to the amateur Montreal AAA team in 1893. Before professional sports teams organized themselves into leagues the cup was competed for by challenging the current winner to a tournament. The first professional hockey team to win the Stanley Cup was the Ottawa Senators in 1901, and in 1926 the Stanley Cup came under the exclusive control of the emerging National Hockey League. In its over 100 years of existence, the Stanley Cup has been awarded in all but two years; the 1918-1919 season in which the Spanish Flu killed 21 million people worldwide, and in the 2004-2005 season when a labour dispute cancelled the entire NHL season. Throughout this period the cup has been lost and stolen, and the original Stanley Cup now sits on display in the Hockey Hall of Fame.

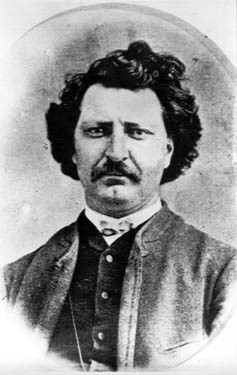

Louis Riel was born in 1844 in Saint Boniface, Red River Settlement, in what is now a part of Winnipeg, Manitoba. At the time, the community was considered a part of Rupert’s Land, administered by the Hudson’s Bay Company. His father, Louis Riel, Sr. was a businessman and political leader in the predominantly Metis community that lived in the Red River Colony, and likely influenced his son’s strong convictions and interest in politics. Riel was the eldest of 11 siblings and his family was well-respected in the community due to Riel Sr’s involvement in local politics and the family’s strong Catholic faith.

Louis Riel was born in 1844 in Saint Boniface, Red River Settlement, in what is now a part of Winnipeg, Manitoba. At the time, the community was considered a part of Rupert’s Land, administered by the Hudson’s Bay Company. His father, Louis Riel, Sr. was a businessman and political leader in the predominantly Metis community that lived in the Red River Colony, and likely influenced his son’s strong convictions and interest in politics. Riel was the eldest of 11 siblings and his family was well-respected in the community due to Riel Sr’s involvement in local politics and the family’s strong Catholic faith.

Young Louis Riel was a standout student from his earliest days attending school, and in 1857, when he was just 13, the Catholic clergy in the Red River community determined that he would make an exemplary priest, and he was offered a scholarship to study at a seminary in Montreal. Wishing to pursue a greater education, Riel set off to Montreal and continued to be an exemplary student and developed a passion for poetry that stuck throughout his life.

In 1864, after learning of his father’s sudden death, and after an engagement to a young French-Canadian woman from Montreal was ended due to her parents’ refusal to allow her to marry a young Metis man, Riel lost interest in the priesthood and moved back to the Red River Settlement, impoverished and distraught. He made his way back out West, working odd jobs in Chicago and St. Paul, Minnesota along the way, arriving back in Red River in 1868 when he was 24 years old.

In 1869, the Hudson’s Bay Company sold Rupert’s Land and the North-West Territory to the Dominion of Canada, to be administered and developed as its leaders sought to expand its territory from sea to sea. The Red River Settlement was comprised of a majority Metis and First Nation people, and upon purchasing the land, the Dominion of Canada sent many land surveyors to determine its suitability for railroad and urban development. The influx of Anglophone Protestant surveyors and settlers from Ontario worried Riel, who believed that their presence would cause linguistic, racial, and religious tension with the predominantly French Catholic Metis and First Nation populations, and because Metis people did not possess true ownership of their land, leading to fear that they would be displaced.

To respond to these concerns the Metis organized the Metis National Committee to represent their collective cause, and the young, educated Riel was elected as its leader after denouncing the land surveys that were to take place in a speech to the Metis community. Under his leadership the Metis National Committee disrupted and put an end to the land surveys using civil disobedience on October 11, 1869. When the regional leadership of HBC summoned Riel to explain his actions, he stated that any attempt by Canada to assert authority over Red River Settlement would be disrupted unless Ottawa negotiated political and land terms with the community first. A month later, Ottawa sent its newly-appointed Anglophone Lieutenant-Governor to Red River, only to be turned back by Metis activists on November 2—the same day a Metis group led by Riel seized Upper Fort Garry—the centre of HBC’s activity in Red River, to prove to Ottawa that the Metis would not back down without a fight. These moments in Canadian history came to be known as the Red River Rebellion, and represent the political beginnings that would result in the entrance of Manitoba into Canadian Confederation.

Following the seizure of Upper Fort Garry, in December 1869 the Metis National Committee established a provisional government led by Louis Riel, and aimed to negotiate fair political and land terms before Ottawa asserted authority over the community. The provisional government issued a declaration on behalf of the people of Rupert’s Land that rejected Canada’s claim of authority over the land, and proposed that a settlement be negotiated between Ottawa and Riel’s provisional government.

The prominence of Riel’s provisional government did not sit well with all of the Anglophone protestant community, and a small group of Scottish Protestants formed with the goal of disbanding the provisional government. This worried the Metis government, and the group was rounded up and imprisoned at Upper Fort Garry. Two of the three prisoners were pardoned, but a third, Thomas Scott, was ordered to be executed by firing squad. On March 4, 1870, Scott was executed despite pleas to Riel that the execution would likely complicate negotiations with Ottawa.

While both Riel’s government and Ottawa downplayed the execution as punishing a difficult individual, Scott’s execution angered much of Protestant Ontario, furious that a Metis Francophone Catholic would summarily execute one of their own. Despite this, on May 12, 1870, the Metis delegates reached an agreement with the Canadian government in the form of the Manitoba Act, and the Province of Manitoba entered into Confederation. The most important part of the Manitoba Act to the Metis was the creation of a 1.4 million acre reserve for their community to continue to live, and a guarantee that the province would be officially bilingual.

Shortly thereafter Ottawa sent a military force, known as the Red River Expedition, to Manitoba as an “errand of peace” however it was not consented to by Riel or the provisional government, and it was not included in the terms of agreement. To Riel and the Metis, it was clear that the force was sent to Red River to hold Riel accountable for his role in the execution of Thomas Scott, and he fled Manitoba to the United States to avoid arrest and likely execution.

While a fugitive, he was elected three times to the Canadian House of Commons, although he never assumed his seat. During these years, he was frustrated by having to remain in exile despite his growing belief that he was a divinely chosen leader and prophet, a belief which would later resurface and influence his actions, and throughout this time he succumbed to mental illness in the form of violent outbursts and displaying signs of megalomania. He married in 1881 while in exile in Montana, and fathered three children.

Riel returned to what is now the province of Saskatchewan to represent Métis grievances to the Canadian government. This resistance escalated into a military confrontation known as the North-West Rebellion of 1885. It ended in his arrest, trial, and execution on a charge of high treason. Many view his execution as a compromise that Prime Minister Macdonald was required to make in order to prevent widespread rebellion and rioting among Anglophone Protestants in Ontario, who continued to despise Riel for his role in Thomas Scott’s execution. Riel was viewed sympathetically in Francophone regions of Canada, and his execution had a lasting influence on relations between the province of Quebec and English-speaking Canada. Whether seen as a Father of Confederation or a traitor, he remains one of the most complex, controversial, and ultimately tragic figures in the history of Canada. Today, Riel is known as something of a Canadian folk-hero for his efforts to safeguard the culture and autonomy of the Metis people.

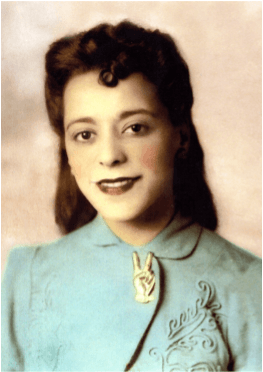

Mary Greyeyes-Reid (1920-2011)

Greyeyes-Reid and service in WWII

Mary Greyeyes-Reid was born on November 14, 1920 in Saskatchewan

Mary Greyes-Reid was the first female Frist Nations member of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. She was part of the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation, just north of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, and was the subject of a famous photo taken in 1942 (below).

In June 1942, following the footsteps of her brother who had already enlisted in military service, she traveled to Saskatoon to enlist as well. As the sergeant told her of her acceptance, she became the first Native American woman to join the Canadian armed forces as a member of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. Although she was the subject of a famous photograph meant to increase recruitment into the military, she would find that she was discriminated against by fellow Canadians, barred from regular barracks and constrained to menial jobs such as laundering or cooking, due to her ethnicity.

The Famous Photo

The title for the photograph—still found in the Library and Archives Canada—says, “Mary Greyeyes being blessed by her native Chief prior to leaving for service in the CWAC”

The title for the photograph—still found in the Library and Archives Canada—says, “Mary Greyeyes being blessed by her native Chief prior to leaving for service in the CWAC”

In late June 1942, within the first month of her military career, several men from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police visited the Piapot reserve, looking to stage a propaganda photograph with Greyeyes. They ran into WW1 veteran and councillor Harry Ball, who agreed to partake in this effort in exchange of 20 dollars.

Pieces of clothing and accessories that might contain Native American flare were borrowed from nearby homes to make Ball appear to be a chief or someone of importance. The resulting photograph, depicting a Native American chief bestowing blessing upon the patriotic and uniformed Greyeyes, quickly became a famous photograph in Canada after first being published in the Regina Leader-Post.

Quickly, the photograph was published all across the British Empire. Somewhere along the way, it gained the official caption of “Unidentified Indian princess getting blessing from her chief and father to go fight in the war”.

It would be many decades before Melanie Fahlman Reid, Greyeyes’ daughter-in-law, could successfully persuade Library and Archives Canada to include Greyeyes’ name in the caption; LAC’s current caption for the photograph would still contain the “chief” description, however.

Despite the newly gained fame, Greyeyes was kept in menial positions. She was shipped out to southern England, United Kingdom to wash laundry and then to cook. As one of the few Native Americans in service in the region, she was often brought to events where diversity was needed, thus she was often seen in newspapers, and she was given the opportunity to meet the Queen Mother, King George VI, and Princess Elizabeth. After the war, Greyeyes returned to Canada in 1946. She passed away in 2011. She was also known by her post-marriage last name of Greyeyes-Reid.

The date of des Groseillier’s arrival to Canada is unknown, but it is likely that he came to Canada in 1641. From 1645-1646 he worked for Jesuits in Huron country. At this time he became proficient in the skills attributed to a coureur des bois—proficiency as a guide, surviving and traveling through the woods, and fur trading to name a few.

The date of des Groseillier’s arrival to Canada is unknown, but it is likely that he came to Canada in 1641. From 1645-1646 he worked for Jesuits in Huron country. At this time he became proficient in the skills attributed to a coureur des bois—proficiency as a guide, surviving and traveling through the woods, and fur trading to name a few.

In 1647 he married his first wife, Helene Abraham, whose father’s land became famous as the Plains of Abraham. In 1653 he married a second wife—Marguerite Hayet, a widow, and the sister of Pierre-Esprit Radisson, with whom he would have a long and productive professional relationship.

A year later, Radisson joined his experienced brother in law des Groseilliers in the fur trade. In 1659, they spent the winter in Sioux country, southwest of Lake Superior, and it was during this time that the two were told of Hudson Bay and the near limitless population of beaver that called it home. They collected many beaver pelts during this mission and in the spring traveled to Montreal, where their furs were confiscated due to their expedition having not been sanctioned by the companies that laid claim to that geographic region.

Following this debacle Radisson and des Groseilliers decided to operate based out of New England and did so from 1662 to 1664. During this time they tried to convince financial backers to cover the cost of their proposed expedition to Hudson Bay, but when ice forced them to turn back from their voyage, their supporters no longer saw the value in financing their expedition. In 1664 they were persuaded that financial backers in London would be more receptive to their proposal, and they set sail there in 1665. When they arrived they arranged to meet with rich and powerful Londoners, and proposed to them a plan to bypass the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes to reach the west, and instead to reach the West by navigating to Hudson’s Bay, of which they had been informed in the Sioux territory years before.

Radisson and des Groseilliers began planning an expedition to prove that this path to the West was practical and possible, and set sail in 1668. Des Groseilliers led with a vessel called the Nonsuch while Radisson commanded the Eaglet, which was forced to turn back from the voyage. Radisson therefore remained in England while des Groseilliers completed the voyage. The Nonsuch successfully traversed Hudson Bay, wintered in James Bay, and returned to England in October 1669 with a cargo of fur that served as proof that the fur trading path to the West through Hudson Bay could be profitable.

As a result of the success that des Groseillier and Radisson’s expedition to Hudson Bay experienced, the British government chartered Hudson’s Bay Company on May 2, 1670. After the company was chartered, Radisson was sent back to North America to establish the company’s Nelson River post and served as a senior guide, translator and travel adviser, while des Groseillier returned home to live in Trois Rivieres.

For reasons unknown, in 1674 Radisson and des Groseilliers became dissatisfied by HBC and defected to the French fur trade after being made a lucrative offer from France to do so. Radisson was never fully trusted by his employers and eventually joined and served the French Navy from 1677 to 1679 while des Groselliers continued continued establishing HBC trading posts along James Bay.

In 1682 both men were hired by French rival to HBC the Compagnie Du Nord to challenge the English monopoly of fur trading in Hudson’s Bay. They traveled down the Nelson River and destroyed the HBC post on Nelson River that Radisson had helped to create. He then created a new post called Fort Bourbon for the Compagnie Du Nord and left it in the command of his nephew & des Groseillier’s son. Des Groseillier then built a French post at the mouth of the Hayes River for the Compagnie du Nord. English complaints of the destruction of their posts by Des Groseilliers and his companions as well as evasion of the French tax on furs again led him into legal trouble with both Canada and France. After unsuccessfully pleading a tax evasion case in Paris (1684) he returned to New France and seemingly retired. As with his brother in law and friend Pierre-Esprit Radisson, Médard Chouart des Groseilliers is an important contributor to Canadian history because his exploits opened up the West to the fur trade and resulted in the foundation of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Nellie McClung was born in Chatsworth, Ontario in 1873, and moved to a homestead in the Souris Valley in Manitoba in 1880 when she was seven years old. She did not attend school until 1883 when she was 10, and performed exceedingly well in the short time that she attended.

Nellie McClung was born in Chatsworth, Ontario in 1873, and moved to a homestead in the Souris Valley in Manitoba in 1880 when she was seven years old. She did not attend school until 1883 when she was 10, and performed exceedingly well in the short time that she attended.

She performed so well at school that when she was 16 she received a teaching certificate and taught children as a school teacher for seven years, before marrying Robert Wesley McClung in 1896. She moved to Manitou, Manitoba with her husband Robert, where he was a pharmacist. There, she became a prominent members of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union at a time when the temperance (anti-alcohol) movement was especially strong in Canada.

In 1908, when she was 35 Nellie McClung published her first novel, called Sowing Seeds in Danny, a “witty portrayal of a small western town” which became a national bestseller and prompted McClung to write a number of short stories and articles in magazines published in both Canada and America.

When she was 38, Nellie McClung, her husband Robert, and their four children moved to Winnipeg, where they had a fifth child. Winnipeg at the time was the heart of numerous social movements, including the worker’s union movements, women’s rights movements, and of course temperance movements, and Nellie McClunh was welcomed by many of them as a speaker who was particularly persuasive to audiences because she used humorous arguments. In 1914 she campaigned actively for the Manitoba Liberal party against Sir Rodmond Roblin’s Conservatives, who refused woman’s suffrage, making a significant foray into partisan politics. McClung and her family moved from Winnipeg to Edmonton in 1915 before her Liberals ultimately unseated the Manitoba Conservatives.

In Alberta McClung continued fighting for female suffrage and for the prohibition of alcohol, worker safety legislation and many other progressive reforms. She gained further prominence as a leading female reformer from conducting speaking tours in Canada and the US, and particularly by being elected as a Liberal Member of the Legislative Assembly for Edmonton and serving in that role from 1921-1926.